Anzu Bird: Exploring an Ancient Mesopotamian Monster

Few non-divine characters are so pervasive across Mesopotamian mythology as the Anzu bird. For millennia, this part-lion-and-eagle demonic creature appeared in countless stories, some of which have survived to the present day in written form.

But what – and who – is Anzu, anyway?

Let’s take a closer look at some of the characteristics of this frightening monster and the many functions it serves in myth, as well as where Anzu fits within a broader, more comparative perspective.

Who Is Anzu?

Like so many mythical figures, it’s difficult to pin down the details of what or who exactly Anzu is and isn’t; its traits depend on the specific myth, inscription, or art piece it’s used in. That being said, there are some universal qualities that it possesses, including:

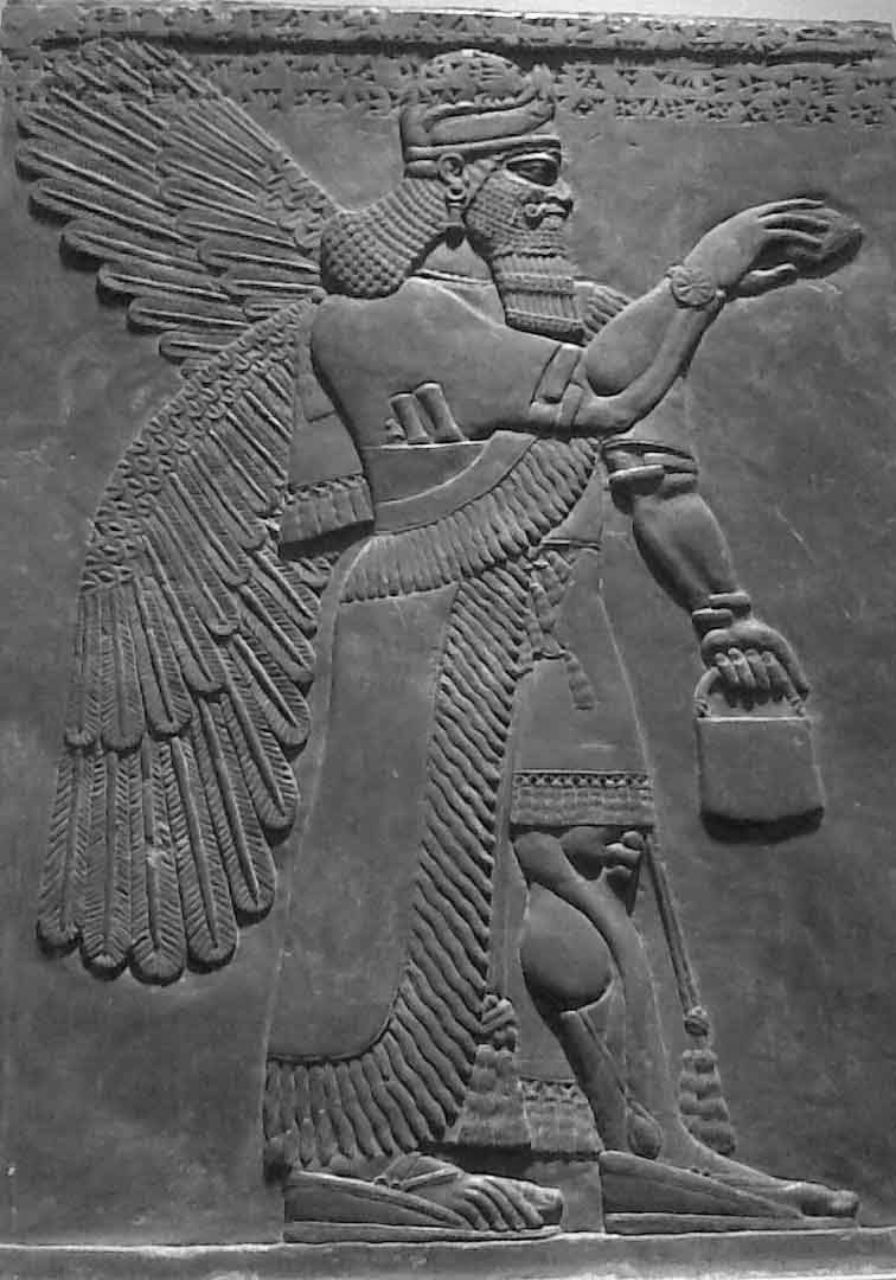

A fearsome physical appearance – oftentimes depicted of a lion-headed eagle

Great supernatural power

It was born from the primordial waters known as Apsu

An association with weather phenomena, like thunderstorms and strong winds

To that last point, Austrian Assyriologist Gwendolyn Leick suggests that Anzu’s primary role in various Mesopotamian mythologies was to represent these weather events’ powers to personify them. In other words, Anzu gives a horrifying face to these unexplainable elements of nature in myths.

Leick goes on to explain that, in literature and art, combined creatures like Anzu are meant to designate “manifestations of demonic forces, which are dangerous but not necessarily evil.”

Demons in Mesopotamian mythology don’t have the same connotations as in more contemporary religious systems, like Christianity or Islam. Instead, they’re more like nature; they are dangerous, but it does not mean they are evil.

Anzu in Mythology

This dynamic can be seen in Anzu’s recurring role in Mesopotamian mythology and epic poetry, especially in his earlier appearances (that we know about, at least). Sometimes Anzu leans more toward transactional benevolence, and sometimes it’s preferred to be evil; that’s just the way it goes.

In terms of source material, three stories warrant a closer look:

The Sumerian epic of Lugalbanda and Enmerkar – the episode in this poem involving Anzu is sometimes known simply as Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird or Lugalbanda II

Another Sumerian myth, The Journey of Ninurta to Eridu

The Babylonian Myth of Anzu and the Tablets of Destiny, which is Anzu’s most well-known appearance in Mesopotamian mythological traditions

Let’s now briefly walk through these myths to see what Anzu is like in each of them.

Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird

Lugalbanda was a Sumerian king of Uruk that turned into a god. He was likely a historical figure, but his adventures in stories most definitely didn’t happen. No gigantic demons live in the remote mountains of Iraq and Iran, where this myth takes place.

Lugalbanda is hopelessly lost in the Zabu Mountains when he decides to visit Anzu and his family to sing their praises and get something in return.

Lugalbanda climbs to the mountain’s peak where Anzu’s chick is nesting and heaps luxuries onto the young monster. Anzu, meanwhile, is out hunting herds of wild bulls.

Upon its arrival, he sees what Lugalbanda has done, for which it is so grateful it bestows great magical power on the king — such as the ability to travel at great speed — but not without the guarantee that people will establish a cult in his honor in Uruk.

The Journey of Ninurta to Eridu

Anzu’s place in this Sumerian myth isn’t as central as it is in the previous one, although it fulfills a similar purpose. Here, a young Anzu leads Ninurta, a god of agriculture, healing, and war, to Apsu, and tells the god his fate. In return for its services, Ninurta promises to create a cult dedicated to Anzu, finished off with a beautiful statue in its likeness.

The Myth of Anzu and the Tablet of Destiny

There are many different versions of this Babylonian myth. Scholars categorize each version chronologically and linguistically; Old, middle, and late Babylonian texts cover roughly 1,000 years.

The story, however, follows the same general plot in each version. The narrative conventions and some of the motifs were influential on later Babylonian mythology, like Enuma eliš, as Assyriologist Selena Wisnom argues in a recent article.

The Standard Babylonian Version begins with Anzu spying on the great god Ellil/Enlil bathing. As soon as the latter is relaxing in the water, Anzu steals away the powerful Tablet of Destiny, which contains Enlil’s power.

The despondent gods chatter frantically amongst themselves to decide who will take on Anzu, ultimately settling on Ninurta (or, in the Old Babylonian version, Ningirsu), who was much more oriented towards war in the Babylonian pantheon.

Ninurta raises an army to take on Anzu and its forces and equips himself with enchanted weapons. At first, nothing works; Anzu uses the Tablet of Destiny’s magical properties to dismantle each of Ninurta’s weapons. Eventually, though, our hero can tire Anzu out enough to cut his wings off and deliver the killing blow, restoring order to the cosmos.

Fragmentary copies of the myth, most of which follow the Standard/Late Babylonian version, have been discovered not just in Babylonian sites but also in former Assyrian cities like Nineveh (present-day Iraq) and Sultantepe in southeastern Turkey.

The Anzu Bird: Its Many Moral Shades

As can be seen from these myths, Anzu ranges from good (in Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird and the Journey of Ninurta to Eridu) to sneaky and evil, as it’s depicted in the final myth.

It’s tempting to look at the cultures from which these myths came from and say that Anzu’s morality in mythology follows a neat historical trajectory, getting meaner and more wicked with each passing civilization. Sure, that might be true — judging exclusively by these myths, that seems to be the case — but there must be more to it than that!

It might be helpful to refresh our memories concerning the major Mesopotamian civilizations and see whether Anzu is a microcosm of the cultural and societal evolution of the area.

Sumerian: existed c. 3500-2400 B.C.

Akkadian: existed c. 2350-2150 B.C.

Old Babylonian: existed c. 2000-1500 B.C.

Middle Assyrian: existed c. 1500-1000 B.C.

Neo-Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian: existed c. 1000-500 B.C.

Anzu appears in both the mythologies and religious systems of each of these different civilizations, as well as their iconography. Perhaps not surprisingly, Anzu is used and understood very differently depending on each distinct culture.

We’ve already seen that, in the extant Sumerian texts, Anzu is more like a terrifying but reasonable force of nature. In contrast, as Gwendolyn Leick explains, Anzu’s evil and threatening side is emphasized in Akkadian art.

In truth, we probably can’t say for sure where Anzu’s morality lay for ancient Mesopotamians. It’s likely (as is the case for most ancient mythologies) that only a tiny fraction of the stories in which we encounter Anzu is available to us.

Part of this is because some written stories or physical art just didn’t make it. But another factor to consider is Anzu’s presence in oral tradition, the stories we tell to other people that we don’t bother writing down; why would we?

People we share stories with generally know what we’re talking about, like who the characters we describe are and why they would behave in a certain way in certain situations. This is probably the case with ancient Mesopotamians, too, and the mythological repertoire they possessed.

Therefore, it’s difficult to ascribe any definite trait to Anzu — or any other mythical beast, anywhere — that would correspond with a given civilization, other than its most essential features.

Some Sumerians might have thought Anzu was an evil demon, not just some manifestation of natural phenomena. Conversely, maybe some Babylonians thought the Tablet of Destiny myth made Anzu look bad and that it was a scary face given to wind and thunderstorms.

Anzu is more complex than what the physical record shows, and, as we’ve progressed into the digital age, this is reflected in forms of media popular today.

World of Warcraft players might recognize the name by an artifact you can find in the Spires of Arak, suitably called the Statue of Anzu. In the game, Anzu serves a different purpose than in mythology. It’s purely aesthetic — a scary eagle sculpture with no real character to it. However, Anzu has clearly never left our collective mindscape.

Anzu and the Comparative Scope

For diehard global mythology fans like myself (and you, hopefully), Anzu might constitute a class of archetypes known as mythological storm birds.

These are large birds — normally predator birds, like eagles, falcons, or hawks — imbued with some kind of supernatural power, usually linked with something to do with storms. This kind of mythical bird appears in mythologies across the world.

Anzu might be considered in this perspective: it is a frightening mix of two dangerous-yet-awe-inspiring animals. However, it seems to exhibit more qualities of an eagle (it flies, lives on mountaintops, has a nest, etc.) than a lion. There is something inherent in an eagle that evokes a healthy dose of fear and respect in so many different cultures.

In this sense, is Anzu the cousin of the Thunderbird from Indigenous American mythologies? Or is Anzu related to griffins from Greek and Roman myth? These are questions that might pop into our heads if we take a comparative approach to Anzu.

We can look past some of the particulars if we decide to go this route and instead focus on the universal characteristics of storm birds worldwide.

Conclusion

Anzu, we think, is an interesting character, regardless of how you want to look at it. In this article, we examined:

Some overview as to who Anzu is in a strictly Mesopotamian context

Anzu’s significant appearances in Sumerian and Babylonian mythology

The nuances of Anzu’s morality in these myths and why it might not be so black and white

Potential approaches of analyzing Anzu in a more comparative perspective

What are your thoughts on the Anzu bird? Do you believe that this mythical creature spawned other fabled storm birds? Well, all we can say is that everyone should be more familiar with this creature and its awesomeness.