Duran, Son of King Arthur

Duran is a very minor figure from the Arthurian legends who appears in just a single source as the son of King Arthur. What is this source and what do we know about him?

Who Was Duran?

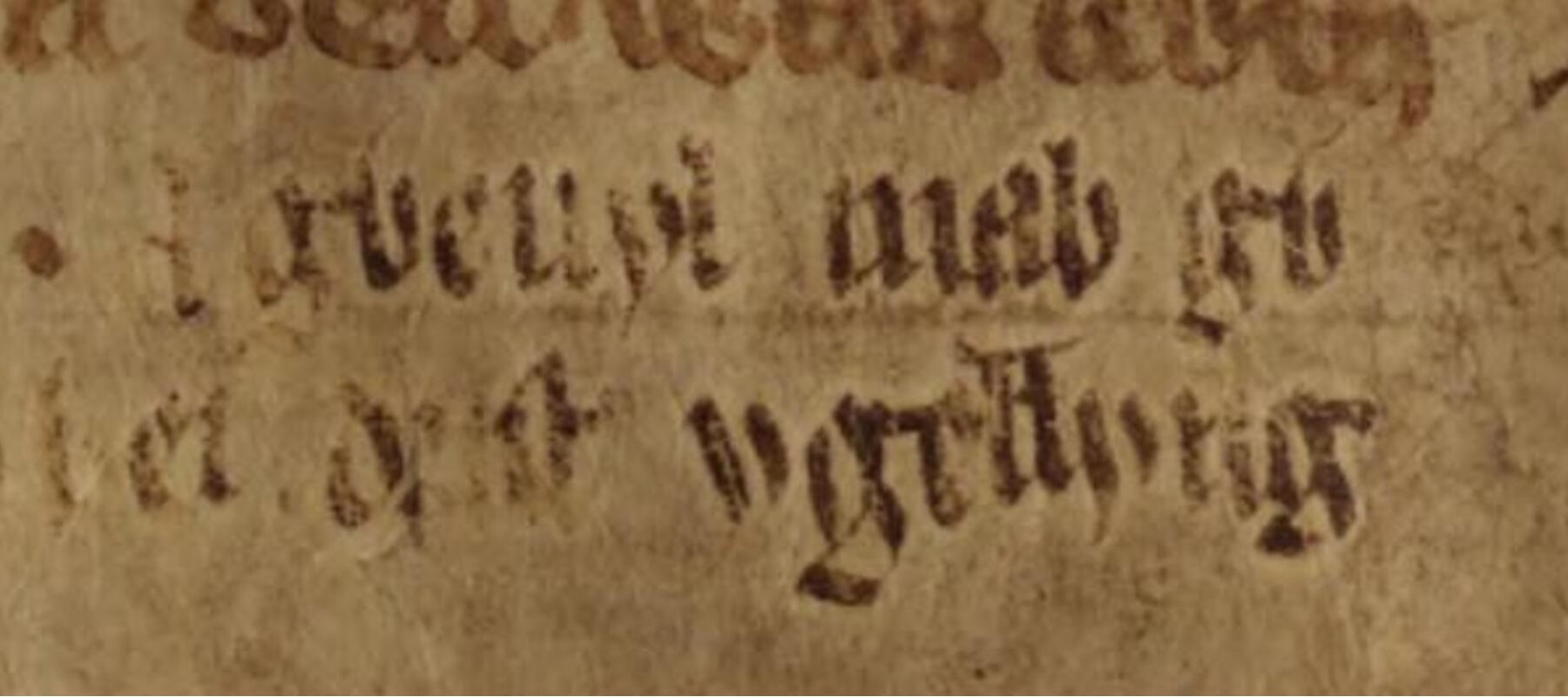

Duran was the son of King Arthur. Yet despite this prominent position, he does not have a major part to play in the legends. In fact, he appears in just a single source. This is a Welsh poem dating to perhaps the fifteenth century, found in a manuscript known as the Mostyn MS 131.

The poem is not entirely about Duran. In fact, it is mainly about a figure named Sandde (or Sanddef) Bryd Angel. The relevant part, translated by scholar Jenny Rowland, says the following:

“Sandde Bryd Angel drive the crow

off the face of Duran [son of Arthur].

Dearly and belovedly his mother raised him.

Arthur sang it.”

This very brief reference to Duran tells us a few things about him. Firstly, he was apparently the son of King Arthur. Secondly, we can observe the fact that Arthur tells Sandde to drive a crow off Duran’s face. Hence, it seems that he is lying dead on a battlefield, where crows would regularly scavenge off the dead bodies. Thirdly, this tells us that Sandde and Arthur were both present at the battle at which Duran died.

Although it is a fleeting reference from only a single source, this information allows us to discern several other things about Duran which are not explicitly stated.

At Which Battle Did Duran Fall?

The poem does not explicitly tell us anything about the battle at which Duran the son of Arthur died. However, the fact that both Arthur and Sandde were there is very useful.

Arthur’s presence indicates that this was one of Arthur’s battles. Presumably, it would have been one of his twelve battles against the Saxons, the Battle of Camlann against his nephew Mordred, or one of the lesser-known battles against the Irish and the Picts.

Sandde’s presence provides a clearer answer. Welsh tradition links him to one battle in particular. In Culhwch and Olwen, a Welsh tale dating to about 1100, Sandde appears as one of Arthur’s allies. Notice how he is described:

“Sandde Pryd Angel – no man laid a spear upon him at Camlan; because of his beauty everyone thought he was an angel fighting alongside them.”

According to this, Sandde was present as a warrior at the Battle of Camlann. This was evidently the battle with which he was most famously associated. Therefore, in view of Sandde being present at the battle at which Duran fell, this likely means that the Battle of Camlann was the battle in question. Indeed, this is the conclusion favoured by most scholars.

Of course, Culhwch and Olwen itself shows that Sandde also participated in the conflict featured in that tale, which seems to take place about two decades before the Battle of Camlann. However, the tale seems quite comprehensive when it comes to describing who died during the events of the story. Duran is not described as dying, nor does he appear at all.

Therefore, the balance of probability favours placing Duran’s death at Camlann over any other battle in the Arthurian legends.

The Tragedy of the Battle of Camlann

The idea that Duran died at Camlann is also consistent with the other pieces of information that we know about this battle. According to all available tradition, it was an awful, bloody battle in which many men died on both sides, including lots of Arthur’s allies.

Assuming that Duran was not simply a late invention, this would also serve to explain why Duran’s death does not appear more prominently in Welsh tradition. It was part of an event at which numerous deaths occurred, rendering Duran’s death comparatively unimportant and unmemorable.

When Was Duran Born?

With Duran’s death quite confidently placed at the Battle of Camlann, what else can we conclude about him? For example, what conclusions, if anything, can we come to concerning when during Arthur’s reign he was born?

The first observation is that, if he was a combatant at the Battle of Camlann, then he surely must have been at least twenty years old at the time. Therefore, we can place his birth about twenty years, at least, before that battle.

The Annales Cambriae places twenty-one or twenty-two years between the Battle of Badon and the Battle of Camlann, depending on which version is used. The former battle was Arthur’s climactic victory against the Saxons, which halted their advance for the rest of his reign. Therefore, Duran cannot realistically have been born more than a year or two after that battle.

Older Than Llacheu

However, evidence from certain other Welsh sources indicates that Duran was born at least several years earlier than that. There are several references to the death of another one of Arthur’s sons, this one called Llacheu. The tradition concerning Llacheu and his death is seen at least as early as Pa Gur, a Welsh poem dating to the ninth or tenth century.

In more than one of these references, Llacheu is specifically described as a youth. This is significant, given that there is good reason for placing Llacheu’s death at about the same time as the Battle of Camlann.

Llacheu’s Death Near Camlann

Two manuscripts, both from the sixteenth century, say that Llacheu was slain at Llongborth. In a much earlier poem, Gereint son of Erbin is said to have died at the Battle of Llongborth, which was a shore battle at which Arthur was present. Meanwhile, the Life of St Teilo places his death at the end of a period of several years in which many Britons from South Wales had been away in Brittany.

Bearing all of these details in mind, it would appear that the Battle of Llongborth can most likely be identified as the initial conflict between Arthur and Mordred upon the former returning to Britain after being away in Brittany for several years.

Other traces of Welsh tradition firmly place Llacheu’s death and his burial near Llech Ysgar in Powys. The site of Camlann can most likely be identified with a site near Dolgellau, which is just next to the medieval border of Powys. The most plausible way of harmonising the two apparently conflicting traditions about Llacheu is that he was severely wounded at Llongborth and then handed over to the men of Powys near Camlann.

This is just some of the evidence that Llacheu died in the conflict between Arthur and Mordred, which conflict culminated at the Battle of Camlann.

What This Means for Duran

Recall that Llacheu is specifically said to have been a youth at the time of his death. As we have established, this appears to have occurred at the same time as Duran’s death.

In contrast to Llacheu, Duran is not described as a youth. Therefore, the balance of probability favours making Llacheu the younger of the two brothers. Llacheu being particularly young would also account for why his death was much better remembered than that of Duran. Presumably, the death of a young prince was viewed as an especially tragic event, in contrast to the death of a grown adult.

On this basis, the most likely conclusion is that Duran was decidedly older than Llacheu. Duran was probably in his late twenties at least, but was potentially quite a bit older.

Younger Than Gwydre

We have seen that Duran was almost certainly older than Llacheu. However, what can we say regarding the other direction? Can we say that he was definitely younger than some of Arthur’s other sons?

As well as Llacheu and Duran, Welsh tradition also assigns Arthur the sons Amhar and Gwydre. The latter appears in Culhwch and Olwen, and there are a number of reasons for concluding that he was the eldest son.

Culhwch and Olwen appears to be set just after the Battle of Badon, after Arthur has already defeated the Saxon enemy Osla but before the period of peace that almost immediately followed, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth. This tale presents Gwydre as active in battle, evidently already as an adult.

Assuming that Arthur was not older than seventy at his final battle against Mordred, putting all this information together would mean that Gwydre must have been born when Arthur was in his twenties. Thus, it is likely that he was the eldest son.

Supporting this is the fact that neither Amhar nor Duran appear in Culhwch and Olwen, despite Arthur being provided with an enormous list of allies.

On this basis, we can probably conclude that Gwydre was the only one of Arthur’s sons old enough to participate in battle at the time in which Culhwch and Olwen is set, just after the Battle of Badon. Just how young Duran was, we cannot know.

Since he apparently was not a youth at the Battle of Camlann, he was probably born at least four or five years before the Battle of Badon. Therefore, he may have been as young as five or six years old when the events of Culhwch and Olwen took place. On the other hand, he could have been as old as his late teens.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that Duran was born when Arthur was between approximately thirty and his early forties.

Absolute Dates for Duran’s Birth

Now that we have seen when Duran was born relative to Arthur, what can we say regarding his absolute dates? Obviously, this depends on the absolute dates assigned to Arthur. There is considerable debate about this, but the Annales Cambriae, a tenth-century chronicle, places the Battle of Badon in 516 and the Battle of Camlann in 537.

If this chronology for Arthur is used, then Duran would have been born somewhere between c. 498 and c. 512, with a death in 537.

Later Chronology

On the other hand, there is growing evidence that the Arthurian dates should be moved forward by several decades. After all, there are a number of examples (seen in the ninth century Historia Brittonum, for example) of dates being mistakenly placed relative to the birth of Jesus when they were originally placed relative to his death.

If this occurred with the Arthurian dates in the Annales Cambriae, this would place the Battle of Badon in about 549 and the Battle of Camlann in 570.

Supporting this conclusion is a very early Welsh poem which describes Aircol as fleeing from Cynan Garwyn. Aircol was the king of Dyfed and the father of Vortipor, a king who was reigning when Gildas wrote De Excidio, forty-three years after the Battle of Badon. Thus, Aircol would logically have been reigning when that battle occurred.

Notably, the reign of Cynan Garwyn, the king who caused Aircol to flee, is firmly placed in the second half of the sixth century. Therefore, Aircol’s reign must have continued until at least some way into that era.

Since his son, Vortipor, was reigning when Gildas wrote De Excidio, which Gildas himself says was forty-three years after the Battle of Badon, that battle must have occurred in about the middle of the sixth century. This would not accommodate the Annales Cambriae’s date of 516 for that event, but it would nicely accommodate the revised date of 549.

Within this revised chronology, Duran’s birth would likely have occurred between c. 531 and c. 545.

Was Duran a Real Person?

One final, important question remains. Was Duran the son of King Arthur a real person? The biggest difference between Duran and Arthur’s three other sons from Welsh tradition is that the source which mentions Duran cannot, in any way, be described as ‘early’.

As we saw earlier, he is only mentioned in a poem dating to about the fifteenth century. This is almost 1000 years after he would have lived. Of course, it is not impossible for traditions to survive that long without any trace of them in between. We see this, for example, in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, which contains a number of accurate traditions concerning the first century CE.

Of course, the absence of Duran from any preceding record is more conspicuous than the aforementioned example, since there is a substantial amount of Arthurian material from the centuries leading up to Duran’s appearance in which he could have appeared, but did not.

On the other hand, Amhar appears in one of the very earliest Arthurian sources, the Mirabilia, yet after that, he only appears in a single other source, a Welsh tale from the twelfth century. Despite the demonstrable fact that he was part of the very earliest Arthurian tradition, he is absent from almost all other sources. Therefore, perhaps Duran’s absence is not so unusual after all.

Furthermore, there is no obvious reason as to why the writer of the poem in which Duran was mentioned would have invented him. If he needed a son of Arthur for the king to lament over, Llacheu and Gwydre were both readily available. The fact that the poet did not choose either of those suggests that the tradition about Duran already existed.

Duran’s Real Name

Another interesting observation is that the name ‘Duran’ does not seem to appear as the name of anyone else in the medieval Welsh texts concerning the Arthurian period. This suggests that it was possibly a corruption of a better-attested name. There are a few possibilities that we could consider.

Diheufyr

The first possibility is that the name of Arthur’s son is connected to a figure called Diheufyr. He appears in a variety of medieval manuscripts, where he is made a son of Hawystl Gloff by his wife Tywanwedd, the daughter of Amlawdd Wledig.

His name is usually shortened in one of two ways. One twelfth century source calls him Deifer. However, a number of other manuscripts use the even shorter form ‘Deir’, which is also used for the name of his holy well. Potentially, the name of Arthur’s son Duran could be a form of this name.

The idea that Arthur may have used this name for his son is supported by the fact that Arthur, like Diheufyr, is said to have been a descendant of Amlawdd Wledig. Hence, this was a name which already existed in his family.

Furthermore, Diheufyr’s father Hawystl Gloff (which is actually a title, ‘Augustulus the Lame’) is identified as Tudfwlch the prince of Cerniw, better known as Teithfallt, in the Descent of the Men of the North. He was the great-grandfather of Athrwys, one of the candidates for the real King Arthur. If Athrwys really was Arthur, this would make Diheufyr his great-uncle, adding to the plausibility of him giving that name to one of his sons.

Tyrnog

A similar possibility is that the name of Arthur’s son Duran is a form of the name ‘Tyrnog’. This name was held by another one of the sons of Hawystl Gloff, or Teithfallt. Therefore, for exactly the same reasons as in the previous entry, it could be argued that this would be a logical name for Arthur to use for one of his sons, given that it was the name of one of Arthur’s family members if we accept the identification of Arthur with Athrwys.

It was common for the letter ‘t’ and the letter ‘d’ to be exchanged, even aside from the normal rules of Welsh phonology. Furthermore, there are many examples of the endings of names being clipped, such as in the name ‘Selyf’, from ‘Salomon’. There are also, occasionally, instances of extra vowels being inserted between consonants.

Therefore, it is within the realms of plausibility that ‘Duran’ (who only appears in a fifteenth-century manuscript, remember) is a late corruption of ‘Tyrnog’.

Dirdan

Another possibility is that the name ‘Duran’ is a corruption or alternative form of the name ‘Dirdan’. This is the name of a figure who appears in a few genealogical records which place him in the late fifth century. He cannot be identified as Duran himself, nor does he seem to have had any notable family connection to Arthur. Still, we cannot rule out the possibility of a connection between these two names.

Twrog

One more notable possibility is that the name ‘Duran’ is connected to Twrog, a figure associated with North Wales in the late-sixth, early seventh centuries. The suffix ‘og’ was written as ‘auc’ in Old Welsh. The letters ‘u’ and ‘n’ were regularly confused for each other. Furthermore, the letter ‘c’ was occasionally mistaken for the letter ‘t’ in the medieval manuscripts. For this reason, the suffix ‘auc’ was sometimes miscopied as ‘ant’.

If this happened in the case of the name ‘Twrog’, it would produce ‘Twrant’. We should also bear in mind that the letter ‘t’ was usually dropped when it came immediately after an ‘n’ (the name ‘Morgan’, for example, comes from ‘Morcant’). The result, ‘Twran’ or ‘Dwran’, is very similar to ‘Duran’, the name of King Arthur’s son.

Alternatively, it could be that the name of this figure is actually a slight corruption of the name ‘Tyrnog’, with the ‘n’ having been dropped. In that case, we could propose the same simple corruption suggested in the entry on Tyrnog the son of Hawystl Gloff.

According to the Dictionarium Duplex of 1632, Twrog was still alive in the time of King Cadfan, who would not have even been an adult, if born at all, by the time of the Battle of Camlann.

Therefore, Twrog cannot be identified as King Arthur’s son Duran himself. Rather, he appears to have lived in the generation after him. This raises an interesting possibility. Perhaps this Twrog was actually named in honour of Arthur’s son. What makes this suggestion even more appealing is that Twrog was active in the northwest corner of Wales. The most likely location for Camlann, where Duran fell in battle, is in this same region.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Duran is an obscure but very interesting figure. He appears to have fallen in battle at Camlann, which was in either 537 or 570. While being the son of King Arthur, he was likely born too late to have participated in the Saxon wars, explaining his general absence from the legends. He was likely the third son of Arthur, after Gwydre and Amhar but before Llacheu.

While we cannot be sure, it is possible that ‘Duran’ is a corruption of a better attested name. A plausible suggestion is ‘Tyrnog’, the name of a figure who was arguably Arthur’s great-uncle. Furthermore, it may well be that a religious figure of the late-sixth, early-seventh century recorded as Twrog and active near Camlann was named after Duran.

Sources

Bartrum, Peter, A Welsh Classical Dictionary, 1993

Bromwich, Rachel, Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain, 2014

Green, Caitlin, Arthuriana: Early Arthurian Tradition and the Origins of the Legend, 2009

Lewis, Barry James, Arthurian references in medieval Welsh poetry, c. 1100-c. 1540, 2019

Howells, Caleb, King Arthur: The Man Who Conquered Europe, 2019

https://clasmerdin.blogspot.com/2019/02/sanddef-pryd-angel.html